[This is from the archives but has been thoroughly re-worked into a two-parter].

What follows is a precis of the story of the thesis that Christianity originated as a psychedelic cult. If the subject sounds crazy, just know that it involves major scholars, political intrigue, some of the most influential public voices in the world today, and even the Pope. These posts are framed around a recent book—Brian Muraresku’s Immortality Key—which I reviewed in Academia Letters a few years back. I summarize the review in Part II of the post, dismantling the historical core of the book.

Here in Part I, I tell the story of a maverick scholar of the dead sea scrolls and a psychedelic trip into a new theory of ancient religion.

Setting the Table

In the summer of 2021 I read a book called The Immortality Key: The Secret History of the Religion with No Name, by Brian C. Muraresku. It’s one in a genre of books that discuss the apparent psychedelic roots of religion/ancient history and cultures—known among its proponents as the “entheogen” thesis of the etiology of religion. I have some interest in these books in general, but those that discuss early Christianity interest me especially. Here’s the story of my foray into a strange field. . .

A Short Cut to Mushrooms

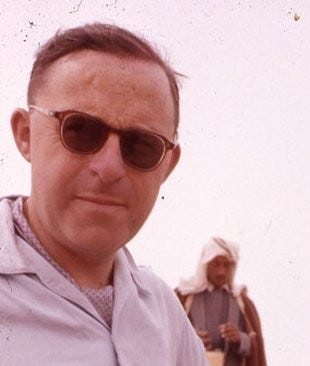

I first became aware of the “entheogen” thesis vis-à-vis Christianity when I encountered the work of John Marco Allegro around ten years ago. I didn’t know then what I know now, but I was, nonetheless, on notice. The story goes back a half century.

It was the 1950s and Allegro was becoming a well-known scholar of the then-newly-discovered Dead Sea Scrolls. He researched at the University of Manchester in the department of Near Eastern Studies. Early books of his like The Dead Sea Scrolls (1956), The People of the Dead Sea Scrolls (1958), and The Treasure of the Copper Scroll (1960)—in addition to public talks—revealed him to be a major expert on the scrolls as well as their most enthusiastic popularizer.

He was an expert, for sure, but by the end of the 1950s his interpretations were becoming controversial. He began to suggest in public, for example, that the crucifixion of Jesus was presaged by the death (apparently by crucifixion) of the “Teacher of Righteousness,” the enigmatic leader of the Qumran community. In addition to his penchant for publicizing, and questions about some of his philological methods, this was enough to cause Allegro’s colleagues in the faculty of arts to distance themselves from him and even create obstacles for his continued research.

Allegro overcame the problems of his faculty by moving to another: the faculty of theology in the Old Testament department at Manchester. Seems a curious move for a would-be rogue, but it was facilitated by none other than the great F. F. Bruce. Bruce had recently (1959) taken up the Rylands Chair of Biblical Criticism at Manchester and had some sway. He apparently believed that Allegro still deserved his academic freedom and sympathized with at least some of his early work on the scrolls—Bruce himself was also an expert in the scrolls and published major research that experts still consider valuable. [This is all detailed in George J. Brooke’s essay “Dead Sea Scrolls Scholarship in the United Kingdom.”]

Allegro, however, was on a track. He was moving swiftly from eccentricity into absurdity, and in the years that followed he began developing a new interpretation of early Christianity. Could Allegro have found a new key to unlocking a hidden meaning behind the Qumran community, early Christianity, and the whole of antique religion? He believed he had. His increasingly eccentric interpretations of the scrolls and increasingly erratic use of Semitic philology became the bread and butter of a new approach. Allegro was becoming many things, but he was no fool: he knew that the publication of these ideas would spell the end of his career as he had known it. He saw the writing on the wall and resigned from his position at Manchester.

Then he published his controversial idea: The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross.

In the book Allegro proposed that Christianity was one of many myths that emerged around devotion to the psychedelic mushroom Fly Agaric (or Amanita Muscaria). And Jesus, the disciples, and other people and places were literary ciphers expressing aspects of the mushroom and the psychedelic experience.

But why?

Well, Allegro had some evidence about the flora and fungi of the ancient world, and knew that some ancient cultures discussed mushrooms of various kinds and had various interests in them. He was also aware of a newly re-discovered psychedelic mushroom—the aforementioned Fly Agaric. And so began the telling of the tale.

What of his method?

Allegro’s methodology is labyrinthine (but this can be typical of comparative philology). Worse, it is irrational and purely hypothetical. It goes like goes like this: Sumerian is said by Allegro to be the bridge language between Proto-Indo European (the hypothetical parent language behind the known Indro-European languages of the ancient world) and the Semitic world. If this is true, then the intermediary etymology for which comparative philologists are so well-known could be undertaken, with potentially new implications for related languages like classical (biblical) Hebrew and ancient Greek. In other words, he could make up new roots for known words and thus give them new meanings.

In his own words: “we can now trace Indo-European and Semitic verbal roots, and so begin to decipher for the first time the names of gods, heroes, plants, and animals. . . We can also now start penetrating to the root-meanings of many religious and secular terms whose original significance has been obscure.” (Sacred Mushroom, p. 42).

The result was a deconstruction of the received knowledge about the origins of Christianity.

French anthropologist Paul Jorion summed up the fallout in his review essay in L’homme (easy to find): “Christ would lose all reality, and would become only the representative of the sacred mushroom in a cryptic discourse (i.e., the Gospels). The other actors of the New Testament would have no more consistency than the protagonist: their proper names or the context of the episodes in which they appear would help to link them directly or indirectly to the divine mushroom.” This is exactly what Allegro proposed.

And Allegro’s creative speculations knew no bounds: Yahweh and Zeus originate with Sumerian terms meaning something like spermatozoa; “Peter” with a Sumerian term meaning “top of the head: penis”; “the most common Semitic name for the mushroom phutr (Arabic), pitra (Aramaic), portrayed in the New Testament myth as Peter.” (p. 66). His phallic-inspired speculations (about mushrooms and their portrayal in myth) go on to include the meaning of “Christ” and a great many other terms in the Bible.

The reception was not so good. The reviews in English, French, German in major journals are almost uniformly negative. The general conclusion? It’s “folk etymology.”

Allegro . . . et al.

Allegro went on to fly his maverick’s flag, and his story is told in various places.

He isn’t just about a curious blip in the timeline of biblical study, however. Allegro’s work did not simply emerge onto the fringe from out of the blue, but actually joined an already-moving reconstructionist machine.

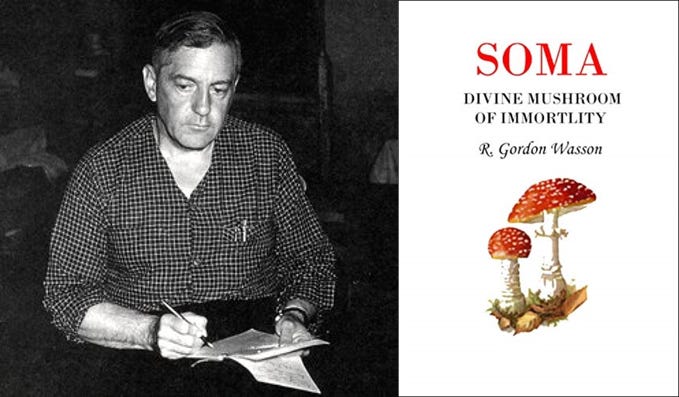

An author by the name of R. Gordon Wasson (an amateur ethnomycologist and vice president of J. P. Morgan) had written a book two years before Allegro’s Sacred Mushroom, called Soma: Divine Mushroom of Immortality. Wasson himself had discovered (or re-discovered) the mushroom Amanita Muscaria and in his book he claimed that “Soma”—the well-known but mysterious beverage of the Vedic texts—was really a concoction of this psychedelic shroom. The mushroom was also responsible for the ecstatic experiences in ancient mystery cults like those of Eleusis, the most famous of the ancient Greek mysteries.

This wasn’t seen as popularist poppycock, and Wasson’s work was actually taken seriously by some scholars of note. The famed anthropologist Claude-Levi Strauss, for example, devoted 12 pages to an extensive review of Wasson’s work, with mixed reception (mixed is fairly positive as far as reviews go). Wasson was also friends with the well-known Slavist and literary scholar Roman Jakobson at Harvard who helped him in his research. Other scholars were favourable too—of the type one might expect. Robert Graves, for example, unsurprisingly was quite taken with Wasson’s thesis (and with psychedelics) and says as much in the updated foreword to his Greek Myths (great reading, if not wholly accurate):

I no longer believe that [the Maenads of Dionysus] . . . had intoxicated themselves solely on wine or ivy ale. . . . the evidence suggests that [they] . . . used these brews to wash down mouthfuls of a far stronger drug: namely a raw mushroom, amanita muscaria, which induces hallucinations, senseless rioting, prophetic sight, erotic energy, and remarkable muscular strength.

And after more commentary on the same, including his own eating of psilocybin, “I thus wholeheartedly agree with R. Gordon Wasson, the American discoverer of this ancient rite, that European ideas of Heaven and Hell may well have been derived from similar [psychedelic mushroom] mysteries.”

Allegro was not alone, then, and it might be said that between him and Wasson, a loose movement was emerging.

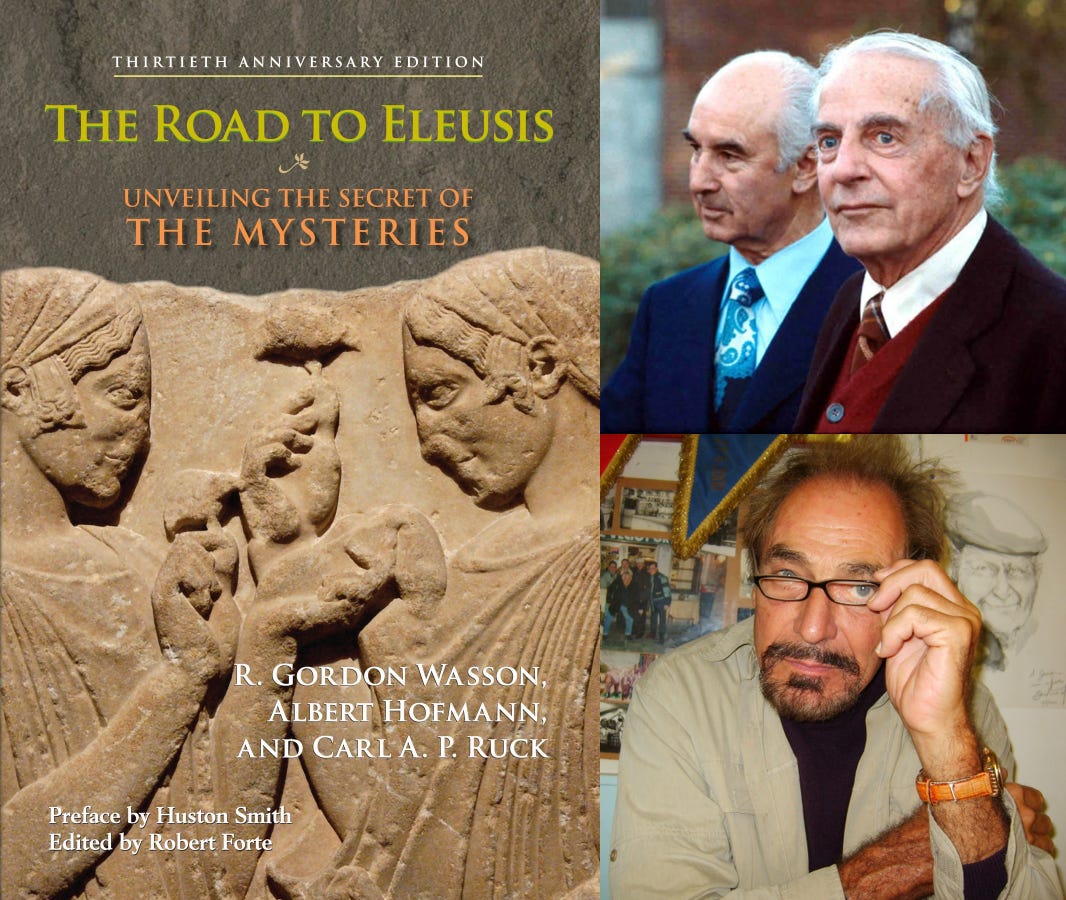

A third man joined the effort, with the needed bona fides of a classicist: Carl A. P. Ruck. Ruck is a major classicist and he had read Allegro in the 70s. Allegro “ruined him”, he said, because he put an idea in Ruck’s head he could not get out: psychedelic drugs featured prominently in classical religious experience. Ruck eventually coined the term “entheogen”, linked up with Wasson, and wrote the now classic text in this fringe of a field.

The Road to Eleusis

Gordon Wasson had already maintained that the amanita muscaria was responsible not only as the substance behind the Soma of the Vedic texts, but also behind other ancient cult practices like the mysteries at Eleusis. This idea sparked Ruck’s interest.

Ruck and Wasson—together with a third author, Albert Hoffman (famous for discovering LSD)—would put these threads together in the book The Road to Eleusis.

What is Eleusis?

Eleusis is a place. It is a town in western Attica in Greece and home to an ancient cult site known simply by the name “Eleusis.” What happened at Eleusis is what matters: the Eleusinian Mysteries.

The cult at Eleusis taught the myth that Hades (god of the underworld) had snatched away Persephone and that her sorrowing mother Demeter, in return for hospitality received at Eleusis during her search for her daughter, revealed secret rites to its inhabitants. These constitute the Eleusinian Mysteries.

The mysteries themselves

“included a type of passion play, probably centering on the suffering of the goddess, a revelation of sacred cult objects, and a communion celebration consisting of a barely drink and certain foods. In this service the initiate supposedly established mystic contact with the mother and daughter. By an act of faith, the initiate believed in the certainty of blessing from Demeter and Persephone in the next life because of the establishment of a friendship with the pair in this life. The main part of the initiation ceremony took place in the Telesterion—the large sanctuary hall—which has been excavated at Eleusis.” (see H. F. Vos. “Greco-Roman Religions,” in the ISBE).

But was it all just faith in a mystic contact with the goddesses? Or was there more substance to the affair? What precisely was going on in the inner chamber inside the telesterion? And what exactly were the “greater mysteries” of the rite?

References to ancient literature do not really help us, but they certainly intrigued the aforementioned authors. Consider Plato (Phaedrus, p. 250 b-c). Plato possibly indicates that the Mysteries were “the blessed sight and vision” “the holiest of mysteries” and seen in “a state of perfection.” This is surmised by Wasson, Ruck, and others, anyway. If you read the Phaedrus text you will find no clear reference to Eleusis but it may be a safe supposition.

A more plausible reference comes from Cicero On the Laws, which contains a fictionalized dialogue between Cicero, his brother Quintus, and their friend Atticus. In book 2 they discuss women’s nighttime rituals and what will become of the “mysteries” if nocturnal rites be removed. Atticus indicates that Cicero and he have been initiated into the mysteries (of Eleusis? probably) and have made an exception for that rite. Cicero replies:

“I will make an exception. Your beloved Athens seems to me to have brought forth many superb and divine things and given them to human life, but nothing is better than the Mysteries through which we have been developed and civilized from a rustic and crude existence into humanity. We recognize the initiations, as they are called, as the true beginning of life, and we have accepted with joy not only this plan for living in happiness, but also a better expectation in death. What displeases me about nocturnal rites is shown by the comic poets. If such license were given at Rome, what would that man have done who brought his lewd plans into a sacrificial rite on which it was a sin to gaze even unintentionally?” Cicero, Laws, 2.36

Evidence like this is intriguing. Paired with art and sculpture—like the “Exaltation of the Flower” pictured above and below—Ruck, Wasson, and Hoffman surmised that some sort of floral or fungal psychedelic may have lied at the heart of Greek mystery cults. It would be the best explanation of the transcendent language of the Eleusinian mysteries and other mysteries besides, they supposed. And since a barley drink was drunk in the greater mysteries, the psychedelics must have been mixed within it.

L'Exaltation de la Fleur By Unknown author - Françoise Foliot, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=86160563

There is a rationale to the argument because ergot, a natural but potentially deadly growth on barley, can produce psychedelic experiences. Hoffman knew this since his discovery of LSD involved the study of barley ergot.

And so, the classic text was born: the mysteries at Eleusis were psychedelic. The reception of Ruck’s et al.’s work was mixed. Several scholars were warm to the idea (e.g., Georg Luck in the American Journal of Philology, 122.1 135-38) while others rejected it as ludicrous.

Most experts have been relatively uninterested in the thesis yet clear in the view that we cannot know what was going on in the greater mysteries. Were the “greater mysteries” truly about immortality? The inimitable Walter Burkert: “no matter how surprising it may seem to one Platonically influenced, there is no mention of immortality at Eleusis, nor of a soul and the transmigration of souls, nor yet deification.” Jan Bremmer adds “in other words, the actual performance of the Mysteries points only to agricultural fertility.” (Bremmer, Initiation into the Mysteries, 18).

There is a perhaps underwhelming sobriety to such scholarship but then that is often the nature of good scholarship.

I actually think that there may well be something to the “entheogen” idea—but not the thesis whole cloth. This is because psychedelic substances are as old as the earth, so to speak, they did then what they do now, and are demonstrably used in religions historically.

But my intention is to consider a realm in which they were clearly not constitutive of the religious experience or generative of the primitive doctrine: early Christianity. I do this in Part II.

Out of Eleusis and into the Church

Christianity was Allegro’s special interest, and while Wasson, Hoffman, and Ruck cavorted over classical landscapes in the Road to Eleusis, later work by Ruck—and the more recent book by Muraresku—bring the focus back to Christianity.

As I say at the outset, Muraresku does so with all the force, funding, and networking of a politician on the campaign trail. He’s met with Rogan, Peterson, and even the Pope! He’s got some friends in “high” places, and claims—more direct to my interests—to have uncovered the secret history of early Christianity in the psychedelic substance of the eucharistic cup.

Is Christian spirituality substance spirituality? The story in Part II starts with Ruck and comes around to Muraresku, where I do a drive-by dismantling of Muraresku’s central claims.